It was psalm 51 that really did it. “Have mercy upon me, O God,” it begins,

according to thy lovingkindness: according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions.

Wash me throughly from mine iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin.

For I acknowledge my transgressions: and my sin is ever before me.

I am not an emotional churchgoer. Inwardly as outwardly, I tend to remain upright, as it were. My usual mode of worship is the contemplation of what you might call abstractions: the “concept” of the Holy Trinity, for instance, or of the doctrine of the Incarnation. The problem here, of course, is that while God in His inmost essence is unknowable, and therefore a kind of abstraction, Jesus was very much knowable. He walked the earth and wept and ate and drank and was touched; and we can known Him even now, in a personal relationship.

Like all Christians, I am always embarking — from the moment of waking to the moment of sleeping and however ineptly — on the adventure of deepening that relationship. But for the longest time I ran away from the hand He held out to me; I fled from the means by which I might grasp it, such as prayer — not the rushed “Our Father” before bed, but the protracted, silent, ardent, disciplined prayer that leads one deeper and deeper into His life. If I had to summarise it in a sentence, I would say that I was scared of meeting someone whose love, forgiveness, and mercy would never alter when it alteration found (to appropriate Shakespeare).

Psalm 51 broke in like a knife. The cantor, an elderly lady with a voice of undiminished purity, sang the above words to the accompaniment of the organ.

Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean: wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

Make me to hear joy and gladness; that the bones which thou hast broken may rejoice.

Hide thy face from my sins, and blot out all mine iniquities.

Create in me a clean heart, O God; and renew a right spirit within me.

Cast me not away from thy presence; and take not thy holy spirit from me.

Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation; and uphold me with thy free spirit.

…

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.

I felt uncomfortably addressed. Not because King David’s sins were my own. (According to tradition, he wrote this psalm after orchestrating the death of Uriah the Hittite (2 Sam 11-12), whose wife he had slept with behind his back; the prophet Nathan chastised David on behalf of the Lord, whereupon he prayed for forgiveness.)

Rather, I identified with the intensity of his wish to be purged. I had spent a decent chuck of my mid-20s with a “broken and contrite” heart. Here in this psalm was the promise that the very fact of my sin was precisely what God would not despise; that he could restore unto me the joy of salvation.

It may seem a strange thing to weep at, this feeling that God forgives you and loves you. Surely (an atheist might say) this is sterling news and one should be happy. But if theology is ultimately analogical, we can see something of the same emotional dynamic in human forgiveness. If you hurt someone and you feel guilty and unworthy of their forgiveness, then if they do forgive you, it can feel like a fresh wound has opened up — though really this is just the sting of healing honey on the same wound. Thus a lot of people paradoxically don’t want to be forgiven; it creates the feeling that your victim has somehow pulled one over you. This was part of Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity: that forgiveness was a means, born of resentment, of undermining your enemies’ ability to hurt you: simply forgive them and they won’t know what to do! Naturally I disagree with Nietzsche, though it stands to reason that some people may feign forgiveness for ulterior motives.

God, however, forgives truly, and his forgiveness is always completely gratuitous, completely in advance of whatever wrong might incur the need for it.

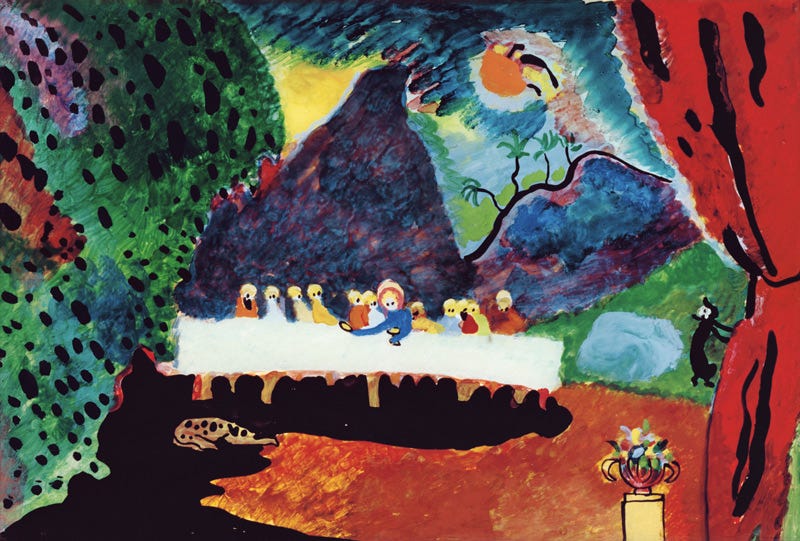

By the time the cantor had stopped singing, I was weeping freely. Soon I was queuing up to receive my blessing from Fr. A (I had been abstaining from the Lord’s Supper until my Confirmation). As the queue shuffled forwards, however, I heard an unmistakeable inner voice telling me to receive the body and blood of Christ for the first time, and not to worry that I wasn’t Confirmed. The voice was saying “It’s OK. You’ve waited long enough. Come, and eat at my table.”

I admit that this voice was unwelcome. Everything about the service so far was unwelcome. I had gone to church with my customary uprightness, expecting to leave at 11.00 sharp, my mind already flitting to the chores that needed doing and the wine I was looking forward to drinking, and the poem I was working on, and Sunday roast — and here I was, disintegrating in real-time and with a decision to make: should I take communion, or not?

For once I decided — with great difficulty — not to overthink it. I was going to make my decision at the final moment.

Looking back, the decision had already been made for me. I couldn’t have resisted even if I’d wanted to; which, as I arrived before Fr. A, I didn’t.

“May I receive?” I whispered, my voice cracking. Fr. A couldn’t hear me, so he leaned closer, a look of concern on his face. “May I receive?” I said more loudly. And then, without a second thought, he handed me a morsel of the body of our Lord and I ate it. I then drank His blood, and was struck by a fresh wave of emotion. I wish I could say that everything suddenly felt all right. It felt better, certainly; but I still felt, to put it bluntly, like one of Cranmer’s “miserable offenders”. (Aren’t we all?) I felt as I imagine Simon did after Jesus lifts him from the stormy sea: safe, sound, loved, but still shivering from the cold and wet. The real healing was to unfold slowly, like a flower.

I had expected to feel guilty about taking communion. I had broken my promise to abstain until Confirmation. My wonderful girlfriend — whose own first-communion experience had been very profound — helped me to understand that what had happened to me had indeed been a “real communion”; and a friend of mine explained that when people break down in church this way, it is said to be the working of the Holy Spirit.

I don’t know. It certainly felt that way.